Survival

of the fittest

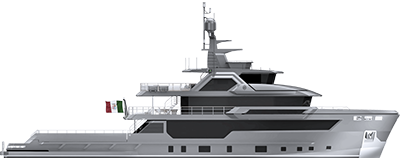

CDM proves that the Darwin series, a niche explorer yacht, can be highly successful, even in a downturn.

Launching a shipyard in the middle of Europe’s worst economic crisis since World War II may not seem like a sensible business strategy, especially given the steep downturn of Italy’s boatbuilding industry. The principals of Cantiere delle Marche (CDM) knew they were gambling when they started their shipyard in August 2010. But they also believed that an unusual yacht design, combined with a new way of production, could work, even in a declining market.

“When we purchased the Ferretti Group’s Custom Line facility in Ancona, many people thought we were committing suicide,” says Vasco Buonpensiere, one of the founders of the fledgling shipyard. “But we believe we’ve found a gap in the market for smaller expedition yachts made out of steel and aluminium. Everything else was made out of fibreglass.”

Buonpensiere and his partner, Ennio Cecchini, had no interest in being the next Azimut or Ferretti Group. Instead, the business plan called for the annual production of four steel-hulled explorer yachts of about 85ft. It was a niche within a niche, but the partners figured there was a market for a tough, intrepid, oceangoing trawler that could be highly customised. They also figured that keeping the business lean, with less than 20 employees working a small production run, would give them enough time to find new clients while also turning a profit. They figured that, for the first years at least, a cautious approach to growth would allow them to maintain quality control while remaining profitable. The partnership was risky, especially at that point in Italy’s freefalling economy.

But there was a history between the new partners. In 2003, Buonpensiere had been a yacht broker, trying to find a shipyard for a client who wanted to build an 82ft steel trawler to cruise the US coast and Caribbean. “At the time, I was looking all over the world for the right yard – China, Estonia, Turkey,” says Buonpensiere. “Then I found it, about 150km from my home.”

Commercial know-how - CNP, a shipyard owned by the Cecchini family, had been in business since the 1950s, first in the construction of pleasure boats, and then building commercial fishing and passenger vessels. Eventually the shipyard became a global leader in constructing chemical tankers, some more than 100m in length. “They were coming from the most complex area of the shipbuilding industry,” says Buonpensiere. “Essentially they were building vessels equivalent to floating bombs. They had to be good.”

The Cecchini yard successfully built the steel trawler for Buonpensiere’s client. Buonpensiere left the brokerage business to take a job as CRN’s sales director during the Ferretti builder’s boom years. After leaving the job in 2010, he was considering an offer from a well-known yard in Northern Europe. “At about that time I received a call from Mr Cecchini,” he says. “He’d sold his shipyard in 2007 and was investing in real estate. But he wanted to get back in the game.”

The ‘game’, as it turned out, would be to buy the just-built Custom Line facility in Ancona, and start the Darwin line of expedition yachts. “We believed that with his knowledge of building complex vessels and my experience in the superyacht world, we could have a viable business,” says Buonpensiere.

Shortly after committing to the idea, he adds, the yard’s first client heard “through the grapevine” about the new shipyard. The two partners commissioned Sergio Cutolo of Hydro Tec, a designer in the explorer-yacht field, to create the first Darwin 86. CDM was in business.

Hull number one, Vita di Mare, was started in August 2010 and delivered in May 2011. About a year later, another Darwin 86 was launched. Percheron became an instant hit with her owner, who put 12,000Nm under the hull in 18 months, including a transatlantic crossing and trips around the Mediterranean and Caribbean. The owner of another 86 also crossed the Atlantic last year, lending proof to the notion that the small Darwins were legitimate passagemakers.

Lifestyle changer - The owner of the first Darwin 96, which was launched in April 2013, also became a valuable marketing tool for the upstart yard by essentially moving on board with his family. After taking over Stella di Mare in April 2013, the owner planned to spend several weeks aboard. Four months later, with only five days in port, he and his family had cruised 5,000Nm across the Mediterranean. The owner, a private-equity investor whose family also owns a large winery in northern Italy, had previously owned a 100ft planing yacht on which he and his family would only spend weekends. But now they were converted liveaboards.

“Two owners have told me that these boats have changed their lifestyles,” says Cutolo, who has gone on to design other explorer yachts in the Darwin series, including a 115-footer. “I don’t think we’ve ever had a higher compliment.”

The yacht was so well received at the Cannes show that it won a World Yachts Trophy for ‘Best Achievement’ in a superyacht. That award put another stamp of legitimacy on CDM’s business strategy. The shipyard now has a full order book through 2016, with a group of international owners from Italy, Germany, Australia, England and Mexico. In late January, it announced the sale of another Darwin 96 to a client in South America. This came three months after Cutolo designed a Darwin 107. The healthy order book, according to Cecchini, is proof that its strategy lives up to the boat’s name. “As Charles Darwin stated many years ago, it is not the strongest who will survive, but the one who will adapt to the changing world,” he said. “We are not the strongest ones, but we have adapted our approach to the design and shipbuilding itself to a market which has changed radically in the last five years.”

Adaptive thinking - While the statement may sound a bit like clever marketing, the CDM founders did employ adaptive thinking when it came to building the Darwin series. Cecchini brought “his best guys” from his former shipyard to comprise his “core” team. Buonpensiere also had good contacts in the local superyacht industry. But they also faced a challenge in the construction of the highly customised interiors. “If you have too many direct employees, you can die quickly because of the labour costs,” says Buonpensiere. “On the other hand, if you subcontract everything, you risk losing control. If you have 10 subcontractors, it’s possible to get two good workers and eight who are just so-so.”

The yard had just 17 employees at the beginning, and recently CDM added more engineers. “Our core team hasn’t changed much from the beginning,” says Buonpensiere. “Our CEO is on board of the boats during construction to make sure everything is going correctly. He’s one of those guys. One of the marine surveyors said it reminded him of a visit to Bugatti, where everyone is motivated and there is very strict attention to detail.”

But 20 workers cannot a superyacht build. In order to solve the subcontractor quandary, the CDM founders hit on a skillful way to assure quality control without the burdensome costs of a large workforce. “We went to two of the main subcontractors in metal, carpentry, piping and joinery who work for some of the best shipyards in Italy,” says Buonpensiere. “And we gave them an ownership stake in the shipyard. Being an owner makes it a matter of pride that their workers do quality work. That means our main contractors are now part of the company.”

The level of work by the two new shareholders, CPN (Costruzioni e Progettazioni Navali srl), which does metalwork, piping and the outfitting of yachts and merchant vessels, and Maurizio Gasparroni, a carpentry firm that has worked on many famous Italian launches, certainly shows in Stella di Mare. IBI visited her at the Cannes show and was impressed by the level of fit and finish as well as the customised interior – the owner’s specifications included a wine cellar for 800 bottles, which the shipyard dutifully built under the VIP stateroom. The exterior looked like a buttoned-down, oceangoing trawler, and the steel under the waterline was 2.5 times thicker than required by the Royal Institute of Naval Architects class standards. The shipyard also used things like copper-nickel piping instead of plastic, and an oil separator in the bilge filters the water before it is discharged, thereby giving the yacht access to many Mediterranean harbours.

Branching out - The yard, realising that the trawler style of the Darwin series might have a limited audience, also launched the Nauta line. The four-yacht series, ranging from 80ft-130ft, came from Nauta Yacht Design, the Italian firm responsible for many superyachts, including the 180m Azzam. “Technically, nothing changes on the boat,” says Buonpensiere. “It’s still as robust as the Darwin line, but it has more of a Navetta look.” The yard sold the first two Nautas from the initial design briefs.

So far, CDM’s business plan has been ticking along nicely, with a new boat sold on average every three months. Five boats have been delivered and another six are under construction. In early February, Buonpensiere said contracts were being prepared for a 106 and 116. “We knew we had something special but we never expected to be this successful this fast,” says Buonpensiere.

Despite the immediate success, the shipyard will stay with its original build plan. “We want to do a maximum of four deliveries per year,” says Buonpensiere. “We have the demand but we still need to build high-quality boats. It’s difficult to maintain that quality when you are building too many.” That’s a problem many Italian shipyards wish they had.